Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings, formerly known as Ditherington Flax Mill, is a historic industrial complex that holds a significant place in the history of the Industrial Revolution. Opened in 1797, it is recognised as the world’s first iron-framed building and is often referred to as the “grandfather of skyscrapers” due to its pioneering construction methods. The complex initially served as a flax mill, producing linen, and later as a malting facility for brewing. Today, it stands as a remarkable testament to architectural innovation and industrial heritage, with ongoing efforts to preserve and restore its unique features.

Key info

| Address | Spring Gardens, Shrewsbury, SY1 2SZ |

| County | Shropshire |

| First opened | 1797 |

| Architect | Charles Bage |

| Ironmaster | William Hazledine |

| Maintained by | Historic England |

| Heritage category | Listed Building (Grade I, II, & II*) |

Visiting guide

Free car park

Café

Toilets

What can I expect when visiting Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings?

You can commence your visit from various locations within the site. In this guide, we shall begin at the south gate, affording a view of the front facade. The verdant lawn in front delineates the original course of the Shrewsbury Canal, which once traversed past the mill. This canal played a pivotal role in the mill owners’ decision to choose this location, as it served as a crucial conduit for receiving raw materials and transporting finished products before the advent of railways.

Proceed through the gates for a closer inspection of the structure. The primary edifice was the original mill, constructed in 1797, housing a substantial Boulton & Watt steam engine to power spinning machinery. In 1810, a southern extension was added, situated to the far left. It accommodated a new 60-horsepower beam engine to operate additional machinery. Take note of the substantial stone blocks halfway up its end wall, positioned between two windows, which supported a weighty beam upon which the steam engine’s ‘rocker beam’ pivoted.

Advance to the front of the building, where you’ll encounter a circular metal grate signifying the location of a chimney erected in 1841. Observe the textured bricks outlining six rectangles, designating the positions of former boilers. These boilers supplied copious amounts of steam to the steam engines propelling the flax mill machinery, filling dye house vats, and drying yarn and thread in the stove house. These boilers and the chimney were dismantled in the late 19th century during the site’s conversion into a maltings. The erstwhile boiler house was repurposed before eventual demolition, leaving the slanted roofline still discernible along the southern face of the kiln in the distance.

Cast your gaze upon the main mill building. Many of the mill’s grand windows were sealed during its transformation into a maltings, while others were resized. This was necessitated to regulate light and humidity, critical factors in the malting process.

We shall now proceed to the rear of the building. As you circumnavigate the south engine house, you’ll encounter the stables and smithy, erected around 1800. These stables housed workhorses responsible for powering the mill, while the blacksmith forged iron tools and mended machine components.

The space to the right of the smithy once accommodated a tall concrete barley silo. Deemed unsafe following a structural inspection, it was razed during the site’s restoration. You can still see it using Google Maps street view from May 2011.

The structure to the right is the stove house, used for drying thread and yarn. The original stove house underwent expansion in the 1840s, constituting much of its current appearance. Take note of the black cat flap on the side. Rats were drawn to the site when it was converted into a maltings due to the presence of barley, prompting the introduction of cats. However, workers started feeding the felines, causing them to cease rat-catching activities. Consequently, the maltings management imposed a prohibition on cat feeding!

Adjacent to the stove house lies the dye house, employed for dyeing thread and yarn. The extant structure, dating from the 1850s, replaced the original dye house and awaits restoration.

Look upward for a view of the Jubilee Tower. Erected in 1897 during the site’s conversion into a maltings, it housed a hoist for transporting grain across all floors and a chute for depositing grain into the kiln, the final phase of the malting process. Its construction coincided with Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, prompting the inclusion of a cast-iron coronet adorned with intricate details, including sunflowers. Manufactured by Macfarlane & Co. of Glasgow, this design was utilized at various UK locations during that era. Although tours of the Jubilee Tower are available, they were unavailable during our visit.

Continue walking past the dye house, around the rear of the site, past the car park. You will notice a solitary building, which served as the apprentice and superintendent’s dwelling. Constructed in 1810, it featured separate dormitories for boys and girls who worked full-time in exchange for their lodging, receiving no monetary compensation. The building also incorporated a dining hall and a schoolroom where education was provided after the children’s shifts. Many of them were sent here from parish workhouses. Later repurposed as a laboratory and worker flats during the maltings’ conversion, it currently awaits restoration.

Proceed past the apprentice house through the expansive archway leading to the kiln. Here, you’ll find the sole remnants of the site’s railway, which once connected to the main line, still paralleling the car park at the rear of the site. The railway extended into the kiln to deliver coal.

As you continue down the corridor, you’ll encounter a coal furnace to your right. Installed during the kiln’s 1960s upgrade, it burned anthracite coal, known for its high heat output and extended burn time. A substantial fan directed hot air upward, ensuring a consistent temperature throughout the kiln.

The next right will lead you into the kiln. Erected in 1897 during the maltings’ conversion, this facility played a critical role in the final stage of the malting process, heating germinated barley to transform it into malt, a key brewing ingredient. Originally designed by Henry Stopes, the kiln was heated by coal furnaces, and its floors consisted of perforated tiles to facilitate heat circulation. Maltsters toiled inside, spreading and turning the grain before shovelling it out. A vanished second floor in the kiln, indicated by the remaining cast-iron support columns, once existed. Presently, the kiln houses lift shafts and staircases, providing access to offices above the ground floor.

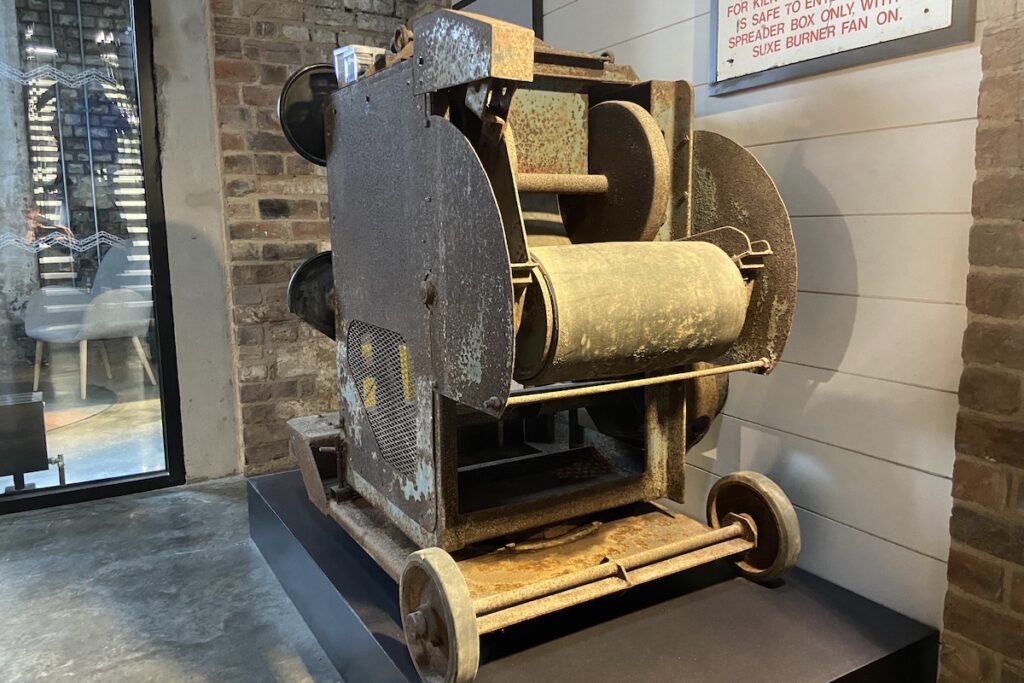

In one corner stands a Redler Bulk Thrower, employed to distribute barley evenly across the kiln floor. Maltsters oscillated it from side to side to achieve a consistent depth. The thrower was stored in an adjacent room when not in use. To the right, a safety sign was posted, warning maltsters of potential hazards within the kiln.

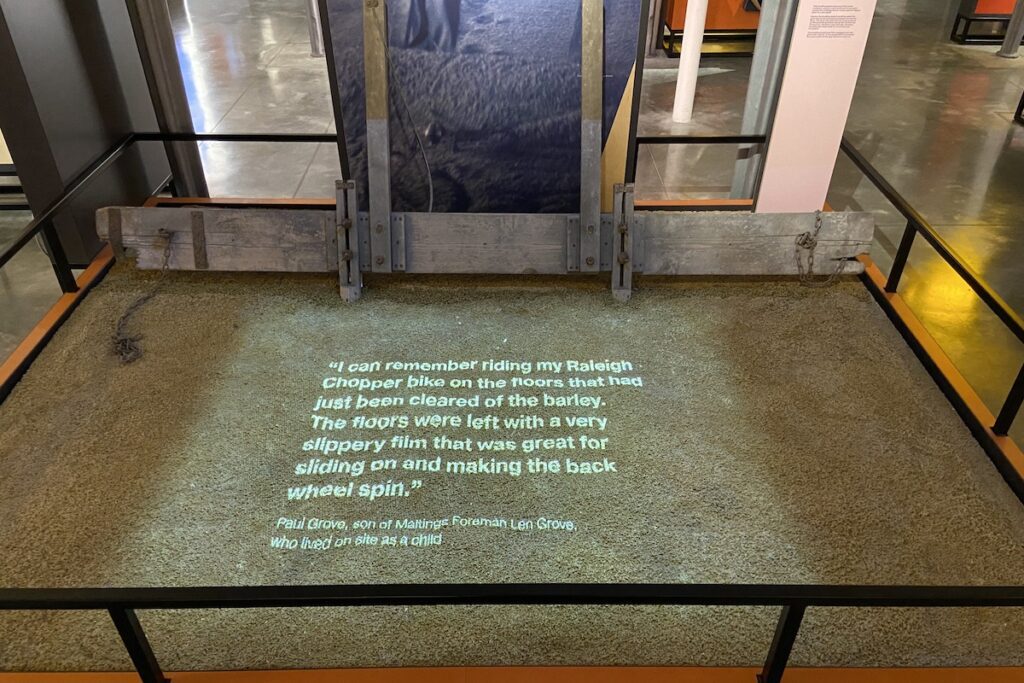

You now have the option to explore The Mill Exhibition, which requires paid admission. It features numerous exhibitions and informational displays chronicling the site’s history. Observe the leveling board on exhibit, used by maltsters to shift and level loose grain across the malting floors, ensuring uniform depth.

At the end of the exhibition hall, the highlight awaits—a glimpse of an original cast-iron column. This is the reason for the site’s significant recognition, as it represents the world’s first cast-iron framed building. Rows of these columns, connected by cast-iron beams, support the floors, with wrought-iron tie rods preventing them from separating. This constituted a fireproof structure. The iron was cast in Shrewsbury by William Hazledine, renowned for supplying engineering projects designed by Thomas Telford.

The exhibition offers much more to explore, beyond the scope of this visitor’s guide. Take your time to peruse the items and delve deeper into the mill’s development and the individuals who worked there. Depart the main exhibition hall through the north engine house, now transformed into a small cinema screening a film about the mill. Adjacent to the exit, another room displays items of interest. Note the original timber beam discovered during restoration work, placed between the brick walls to support the ends of the cast-iron beams. Although no timber was exposed in open spaces, its internal use demonstrates how Charles Bage, the designer of the mill had not quite grasped how to use solely iron and bricks. This highlights the revolutionary nature of this structure at a time when designers like Bage were breaking away from traditional building techniques.

During our visit to Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings, we were fortunate to book a behind-the-scenes guided tour, granting us access to the third floor. This offered a unique opportunity to view the mill/maltings floor in its original layout, as other floors have been partitioned into offices. The cast iron beams between the columns and wrought iron tie rods are clearly visible. Notice the distinct beam running along the width of the space, marking the boundary between the original mill constructed in 1797 (to the right), and its extension after 1804 (to the left). In summary, 204 columns of different designs and 136 beams were required for the mill. The beams, in particular, required precise and complex casting, especially where they fitted with the columns, the walls, and the machinery.

The tour concluded with a visit to the Cross Mill. Originally constructed with a timber frame as an extension of the original cast iron framed mill, it was destroyed by fire in 1811 around the time gas lighting was installed. It was subsequently rebuilt with a fireproof iron frame, and the structure is currently awaiting restoration. It provided us with a glimpse of what the building would have looked like after the maltings closed in 1987, with numerous items from its malting years on display.

To conclude your visit, you may wish to visit the café for coffee and cake.

How long does it take to visit Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings?

You will require about 30 minutes to see the building and another 30 minutes to view The Mill Exhibition. If you take a behind-the-scenes guided tour, that will take around 1 hour in total excluding a visit to the exhibiton.

How do I get to Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings?

Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings has free car parking at the rear albeit there is a time limit, check their website for further information. There is a bus stop opposite the main entrance on St Michael’s Street with services to and from Shrewsbury town centre stopping at Shrewsbury Railway Station, which is about a 20-minute walk from the mill.

History of Shrewsbury Flaxmill Maltings

1781 – The Iron Bridge is opened to the public near Shrewsbury in the Ironbridge Gorge. It is the first road bridge in the world to be made out of cast iron and soon catapults Shropshire into global fame as an innovative hub of iron production.

1793 – Two brothers, Thomas and Benjamin Benyon, who were Shrewsbury wool merchants, formed a partnership with entrepreneur John Marshall of Leeds who wanted to increase his capital. Marshall, a mill owner, was pioneering the mechanisation of flax spinning and had done business with the Benyon brothers previously [1].

1795 – The partnership invested in a flax mill in Leeds, which subsequently burnt down costing them a substantial amount. Mill fires were common at the time due to the use of timber as a building material and the inflammable nature of the materials used in spinning and weaving, especially since the introduction of steam engines to power machinery.

1796 – The partnership decides to invest in a new mill in Ditherington on the outskirts of Shrewsbury. Keen to avoid further losses from fire, the partnership engage with Charles Bage, a resident of Shrewsbury, to design a fireproof building. Bage was an unlikely choice. He had made a living as a wine merchant and surveyor; however, his father, was a partner in an ironworks at Wychnor, Staffordshire, and was a member of the Derby Philosophical Society. The society deputy was one William Strutt, a mill owner from Belper, Derbyshire, who was the first to utilise cast iron components in the construction of mills, most notably cast iron columns supporting timber beams. Charles Bage, through his father, became friends with Strutt, and initiated correspondence in 1796 asking for advice on the construction of the new mill at Shrewbury. It is clear that Bage was already conversant with the latest thinking on using iron as a structural material in textile mills from the content of these letters.

1797 – The new flax mill at Shrewsbury is opened and became the first cast iron framed building in the world. In addition to cast iron columns and brick arched floors pioneered by William Strutt in Derbyshire, Charles Bage, used cast iron beams between the columns. He also contributed to the theories and mathematical formulae to test the strength of cast iron columns. Said theories were developed partly by experiments, some later were carried out by William Hazledine, who manufactured the iron components used in the new flax mill. If the appointment of Bage as architect and engineer appears to be a gamble, commissioning Hazledine to produce the ironwork would also seem to have been rather risky. His foundry at Coleham, across the river from Shrewsbury, had only been in operation for 3 to 4 years, and there is no evidence that Hazledine had attempted anything on this scale before. Nonetheless, samples of ironwork from the mill have been tested with modern methods, which confirmed it was made with exceptional quality [2].

1800 – The stables and smithy are constructed to provide housing for the horses used in the working of the mill and for a blacksmith to repair machine parts and make other iron tools or equipment.

1804 – Thomas and Benjamin Benyon and Charles Bage leave their partnership with John Marshall to set up two new flax mills, one in Leeds and the other in Shrewsbury. Both use cast iron frames and steam engines. Management of the original flax mill at Shrewsbury is then transferred to on-site managers who report to Marshall at his headquarters in Leeds

1810 – The south engine house is added to the mill to house a new 60 horsepower beam engine to supply more power for running more machines.

1811 – The cross mill, a timber framed structure built as an extended wing of the original mill, is destroyed by fire. It was quickly rebuilt using a fireproof cast iron frame.

1813 – The flax mill employs 433 people, including women and children.

1820 – The north engine house is rebuilt so it can accommodate a more powerful engine. A huge wrought iron water tank is mounted to the roof and a cast iron pipe drew water direct from the Shrewsbury Canal.

1840s – The stove house is extended, and the number of employees rises to 800. Two boiler houses were constructed covering the entire terrace area. Each boiler house contained three boilers to generate more steam for the engines, dye house vats, and heating and drying yarn.

1841 – A large chimney stack is constructed to deal with the increased output of smoke from the mill.

1842 – A gas retort house is constructed on the northern part of the site for producing gas by heating coal that was used for lighting the mill.

1845 – John Marshall dies, and the operation of the flax mill continues to be run by his sons.

1850s – The dye house was completely rebuilt with an elegant lightweight wrought iron roof.

1886 – The flax mill closes due to shifting consumer demand from linen to cotton and a lack of interest from later generations of the Marshall family. Machinery and equipment was auctioned off.

1897 – After 10 years of dereliction, the flax mill is bought by William Jones, a maltster looking to expand his business ‘William Jones & Son’. He immediately starts converting the site into a maltings. Many large windows are either bricked up or reduced in size to control the amount of light and humidity. The kiln is constructed to heat germinated barley turning it into malt. The jubilee tower is also constructed to house a grain host and chute. The tower is adorned with a cast iron coronet to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. The designs for the maltings conversion were done by Henry Stopes, a leading authority on malt and malting at the time.

1900 – The hoist tower is constructed to house machinery that lifts sacks of grain up to all floors and a cast iron water tank. The maltings employs around 40 men, a much smaller workforce than the flax mill.

1923 – William Jones dies.

1933 – The company Williams Jones & Son goes bankrupt and taken over by administrators who continue run the business.

1939 – The maltings is temporarily converted into a facility for housing and training soldiers during World War Two. One wall of the canteen was dedicated to The Maltings Gazette, a newspaper that kept soldiers up to date on life in the camp.

1948 – The maltings is taken over by Birmingham brewers Ansells along with other sites formerly owned by William Jones & Son. Ansells later are taken over by Albrew Maltsers Ltd, the arm of major brewing company Allied Breweries responsible for producing malt.

1953 – The main mill was first designated as a Grade I listed structure.

1960s – A new period of increased efficiency and expansion began and output increased six-fold. This includes the construction of a concrete barley silo and malt screening house.

1962 – Professors A. W. Skempton and H. R. Johnson from Imperial College, London published an article proposing the main mill was the world’s first building with a complete iron frame. Historians had previously through Salford Twist Mill, built around 1800, was the oldest.

1987 – The maltings closes due to the floor malting process being unable to compete with modern factories. The site’s future was uncertain. Some saw it as an eyesore and called for it to be demolished. It took a dedicated team of conservators, funders, councillors, and enthusiasts, all collaborating to save the site.

2005 – After another extended period dereliction, the site is bought by English Heritage (now Historic England) and joined forces with Shrewsbury and Atcham Borough Council to prepare a plan for its revival.

2014 – Restoration commences, starting with the smithy and stables.

2017 – Restoration of the main mill and the kiln commences largely thanks to a £20.7 million grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

2019 – The coronet is restored, and the huge chimney base is excavated.

2020 – The south engine house and Jubilee tower is restored.

2021 – A new roof for the cross mill is completed.

2022 – Restoration of the main mill and the kiln is completed, and the site opens to the public.

Sources

- Museum information boards.

- Pattison, A. (2017) William Hazledine Pioneering Ironmaster. Alcester: Brewin Books.

Lower & Upper Neuadd Reservoirs

Lower & Upper Neuadd Reservoirs