Liverpool Old Dock

Liverpool Old Dock marked a transformative moment in maritime history as the world’s first commercial enclosed wet dock. Nestled within the heart of Liverpool, this revolutionary infrastructure bolstered the city’s emergence as a dominant maritime hub, playing an indispensable role in global trade and the growth of the British Empire. Over time, it evolved into a bustling nexus of activity, where goods from far-flung lands were routinely unloaded and shipped. Though eventually buried in 1826 due to advancements and expansion, its rediscovery in the 21st century stands as a testament to Liverpool’s rich maritime heritage.

Key info

| Location | Liverpool |

| County | Merseyside |

| Completed | 1715 |

| Engineer | Thomas Steers |

| Maintained by | National Museums Liverpool |

Visiting guide

Paid car parks

Toilets

What can I expect when visiting Liverpool Old Dock?

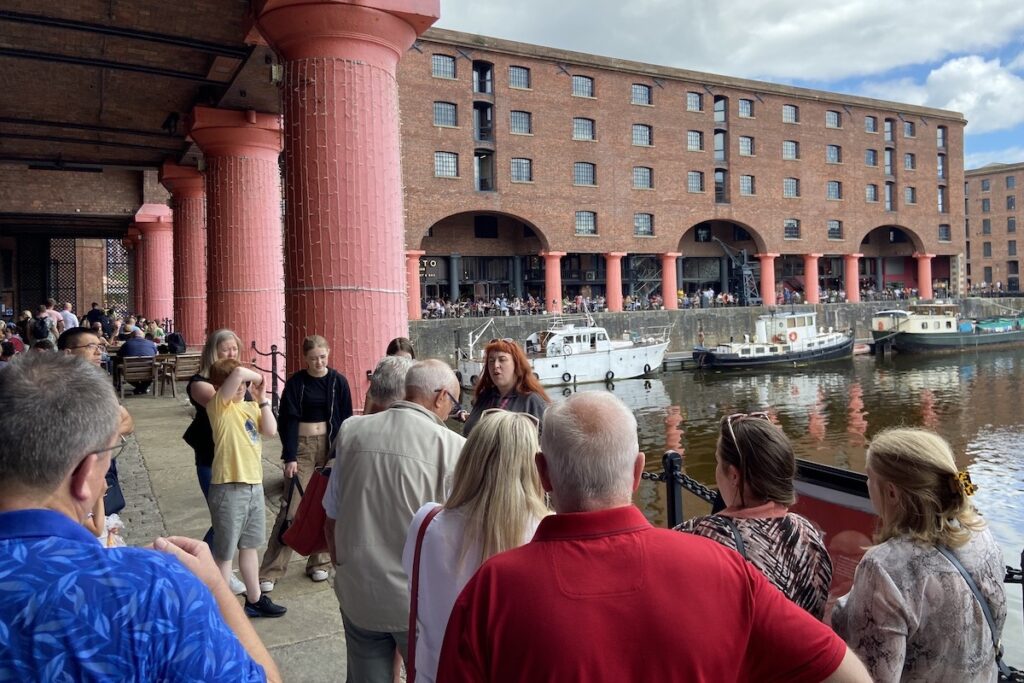

Tours of the Liverpool Old Dock necessitate advance booking through National Museums Liverpool. Your tour commences at the rear entrance of the Maritime Museum situated on the Royal Albert Dock, where a guide will greet you.

You’ll then proceed north-east towards Salthouse Quay, a primary vehicular access into the Royal Albert Dock. To the left of the gates before you was the original entrance to the Liverpool Old Dock. As the city flourished, additional docks emerged, taking land from the River Mersey, with the Canning Dock still present to the left.

Upon crossing The Strand, you’ll be met by Thomas Steers Way, characterised by its black tiled pavement. This pathway traces the former location of the Liver Pool’s mouth, a tidal pool that extended deeply into the city and inspired Liverpool’s name. This pool was infilled during the Old Dock’s creation and has been obscured by urban sprawl.

Observe the inscribed pavement stones – a tribute to William Hutchinson. Having served with the East India Trading Company and as a privateer, he became the Old Dock’s dockmaster in 1759. For 29 years, Hutchinson meticulously logged tidal patterns, aiding the creation of Holden’s Tide Tables in 1770, Britain’s inaugural public tide logbook. These tables were of unparalleled precision, utilised until the 1970s.

We now head underground down to the dock through the Liverpool ONE car park.

You will pass through a room with a map of the city detailing the location of the Liver Pool before descending multiple staircases and crossing a raised walkway over the dock wall. Construction of the old dock lasted 5 years and was a hard work in damp, muddy conditions worsened by the potent currents of the Mersey occasionally breaking through the protective dams.

Head to the end of the raised walkway for a view of the northeast corner of the dock. Notice the bedrock underneath the wall that was dug out by hand to deepen the basin. The dock wall is made out of handmade bricks from clays directly sourced from the Mersey. Excavation of the dock revealed multiple kilns along the riverbed indicating production was done on site.

The bricks were laid using Flemish or English bond with a special lime mortar (developed by a local bricklayer by the name of William Bibby) that provided greater strength and water resistance than conventional mortars. Despite this, the bricks were soft and easily damaged by the ships as they docked. You can see several areas of impact and many indications of repair.

Take note of the small arch at the base – believed to be a 13th-century sally port or hidden passageway stretching 200 ft to Liverpool Castle. This arch was subsequently sealed during the dock’s construction, later accommodating a wooden sluice gate for sewage that is still visible. Consequently, the Old Dock essentially became a cesspool, an issue aggravated as new docks were constructed around it. Instead of sewage being carried out to sea by the Mersey as originally intended, newer adjacent docks created a tidal barrier thus creating a backlog of excrement in the Old Dock. This occasionally trapped ships within due to the sheer volume of waste.

Can you spot the square grooves cut into the bedrock? They would have accommodated vertical fender beams supporting timbers attached horizontally to the dock wall forming a scaffolding like structure as a protective layer to minimise damage from ships. Coupled with the sturdy coping stones and Bibby’s lime mortar, they safeguarded the dock.

From the entrance staircase, admire the view, particularly the concrete foundation supporting the Liverpool ONE complex overhead. Only the north-east section of the dock wall remains visible, showcasing its most intriguing features.

As you re-emerge, consider glancing down the borehole at Thomas Steers Way’s northern end, which reveals the dock’s depth below the contemporary street level.

How long does it take to visit Liverpool Old Dock?

The tour lasts roughly 90 minutes. It’s imperative to remain with your guide throughout. Toilet facilities are available at the entrance.

How do I get to Liverpool Old Dock?

Your journey begins at the Maritime Museum on the Royal Albert Dock, merely a 5-minute stroll from Liverpool James Street railway station. Bus stops, offering routes to the city centre, are located on Salthouse Quay adjacent to the museum. If travelling by car, consider utilising one of the nearby pay-and-display car parks.

History of Liverpool Old Dock

1699 – A wet dock is first proposed by the merchants of Liverpool to speed up the loading and unloading of ships. Before the dock was built, ships were moored in the River Mersey, and cargo was transported via small boats to shore. This cumbersome process typically took up to 2 weeks and was also dependent on the tide.

This is also the year that Howland Great Wet Dock was completed in London, the world’s first privately owned wet dock. One Thomas Steers lived nearby in Rotherhithe and leased some land near the dock from its owner. It’s fair to say he must have seen the wet dock and been inspired by its revolutionary design. Steers then moved to Liverpool at some point by 1709.

1708 – Liverpool Member of Parliament Thomas Johnson, a merchant and slave trader, asks George Sorocold, a notable civil engineer who had worked on the construction of Howland Dock, for a solution on improving maritime unloading times on the Mersey. Sorocold recommends the construction of a wet dock, which was supported by Liverpool Corporation, the local government entity that existed at the time.

1709 – Richard Norris, a Member of Parliament, merchant, and slave trader spearheads a campaign for raising funds and support for the construction of the dock. Construction was to be funded by merchants and Liverpool Corporation, who mortgaged vast amounts of land it owned. Thomas Steers is commissioned to design and construct the dock. He proposes the dock site be located at the mouth of the Liver Pool, a muddy tidal inlet of the Mersey.

1710 – Construction begins, which involved damning the River Mersey, so it did not spill into the Liver Pool, thereby permitting workers to fill in the pool and excavate the dock. Silt and clay were removed by hand while the natural bedrock was dug out to deepen the dock basin. Conditions were damp and muddy. The Mersey on occasion would breach the dams and spill into the construction site, increasing the difficulty of the construction project.

Brick dock walls were constructed on the bedrock and pinned into the land behind. The bricks were made from local clays and fired in kilns at the dock site. The bricks were laid using Flemish or English bond with a special lime mortar (developed by a local bricklayer by the name of William Bibby) that provided greater strength and water resistance than conventional mortars. The walls were protected from ship damage with sandstone coping stones and wooden fenders supported by posts driven into the bedrock.

1715 – The old dock opens, although construction continues.

1716 – Construction is completed.

1722 – The first Custom House opens at the east end of the old dock.

1737 – A dry basin is constructed to enlarge the old dock.

1826 – The old dock closes on the 111th anniversary of its opening. It had continued to attract vessels, but some had argued the dock was too small and not suitable for larger ships. By this point, multiple newer and larger docks had been constructed using better materials and design. The old dock was also becoming more of an open sewer, which impacted maritime activity. A report for the Dock Committee said the quays were too narrow and that a new, larger Customs House should be built on the site to accommodate Liverpool’s increase in trade. The dock is backfilled.

1839 – The new Custom House opens on the site of the old dock.

1941 – Custom House was hit during a bombing raid by German aircraft during World War II.

1948 – Custom House is demolished to make way for development.

1960 – Steers House, a commercial building is constructed on the site of the old dock.

1999 – Steers House is demolished.

2000-09 – Excavations around the old dock identify the surrounding walls.

2009 – Construction of Liverpool ONE, a shopping, residential, and leisure complex is completed on top of the old dock site. Most of the old dock is reburied during construction except the northeast corner, which is left open for development into a new tourist attraction.

2010 – Tours of the Liverpool Old Dock begin coinciding with its tricentennial.

Sources

Historical content sourced from museum information boards.

Cyfarthfa Leat & Gurnos Tramroad

Cyfarthfa Leat & Gurnos Tramroad